Saturday, 15 March 2003

President's Radio Address (Remembering Halabja)

THE PRESIDENT: Good morning. This weekend marks a bitter anniversary for the people of Iraq. Fifteen years ago, Saddam Hussein's regime ordered a chemical weapons attack on a village in Iraq called Halabja. With that single order, the regime killed thousands of Iraq's Kurdish citizens. Whole families died while trying to flee clouds of nerve and mustard agents descending from the sky. Many who managed to survive still suffer from cancer, blindness, respiratory diseases, miscarriages, and severe birth defects among their children.

The chemical attack on Halabja -- just one of 40 targeted at Iraq's own people -- provided a glimpse of the crimes Saddam Hussein is willing to commit, and the kind of threat he now presents to the entire world. He is among history's cruelest dictators, and he is arming himself with the world's most terrible weapons.

Recognizing this threat, the United Nations Security Council demanded that Saddam Hussein give up all his weapons of mass destruction as a condition for ending the Gulf War 12 years ago. The Security Council has repeated this demand numerous times and warned that Iraq faces serious consequences if it fails to comply. Iraq has responded with defiance, delay and deception.

The United States, Great Britain and Spain continue to work with fellow members of the U.N. Security Council to confront this common danger. We have seen far too many instances in the past decade -- from Bosnia, to Rwanda, to Kosovo -- where the failure of the Security Council to act decisively has led to tragedy. And we must recognize that some threats are so grave -- and their potential consequences so terrible -- that they must be removed, even if it requires military force.

As diplomatic efforts continue, we must never lose sight of the basic facts about the regime of Baghdad.

We know from recent history that Saddam Hussein is a reckless dictator who has twice invaded his neighbors without provocation -- wars that led to death and suffering on a massive scale. We know from human rights groups that dissidents in Iraq are tortured, imprisoned and sometimes just disappear; their hands, feet and tongues are cut off; their eyes are gouged out; and female relatives are raped in their presence.

As the Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, said this week, "We have a moral obligation to intervene where evil is in control. Today, that place is Iraq."

We know from prior weapons inspections that Saddam has failed to account for vast quantities of biological and chemical agents, including mustard agent, botulinum toxin and sarin, capable of killing millions of people. We know the Iraqi regime finances and sponsors terror. And we know the regime has plans to place innocent people around military installations to act as human shields.

There is little reason to hope that Saddam Hussein will disarm. If force is required to disarm him, the American people can know that our armed forces have been given every tool and every resource to achieve victory. The people of Iraq can know that every effort will be made to spare innocent life, and to help Iraq recover from three decades of totalitarian rule. And plans are in place to provide Iraqis with massive amounts of food, as well as medicine and other essential supplies, in the event of hostilities.

Crucial days lie ahead for the free nations of the world. Governments are now showing whether their stated commitments to liberty and security are words alone -- or convictions they're prepared to act upon. And for the government of the United States and the coalition we lead, there is no doubt: we will confront a growing danger, to protect ourselves, to remove a patron and protector of terror, and to keep the peace of the world.

Thank you for listening.

In the late morning of March 16, 1988, an Iraqi Air Force helicopter appeared over the city of Halabja, which is about fifteen miles from the border with Iran. The Iran-Iraq War was then in its eighth year, and Halabja was near the front lines. At the time, the city was home to roughly eighty thousand Kurds, who were well accustomed to the proximity of violence to ordinary life. Like most of Iraqi Kurdistan, Halabja was in perpetual revolt against the regime of Saddam Hussein, and its inhabitants were supporters of the peshmerga, the Kurdish fighters whose name means "those who face death."

A young woman named Nasreen Abdel Qadir Muhammad was outside her family's house, preparing food, when she saw the helicopter. The Iranians and the peshmerga had just attacked Iraqi military outposts around Halabja, forcing Saddam's soldiers to retreat. Iranian Revolutionary Guards then infiltrated the city, and the residents assumed that an Iraqi counterattack was imminent. Nasreen and her family expected to spend yet another day in their cellar, which was crude and dark but solid enough to withstand artillery shelling, and even napalm.

"At about ten o'clock, maybe closer to ten-thirty, I saw the helicopter," Nasreen told me. "It was not attacking, though. There were men inside it, taking pictures. One had a regular camera, and the other held what looked like a video camera. They were coming very close. Then they went away."

Nasreen thought that the sight was strange, but she was preoccupied with lunch; she and her sister Rangeen were preparing rice, bread, and beans for the thirty or forty relatives who were taking shelter in the cellar. Rangeen was fifteen at the time. Nasreen was just sixteen, but her father had married her off several months earlier, to a cousin, a thirty-year-old physician's assistant named Bakhtiar Abdul Aziz. Halabja is a conservative place, and many more women wear the veil than in the more cosmopolitan Kurdish cities to the northwest and the Arab cities to the south.

The bombardment began shortly before eleven. The Iraqi Army, positioned on the main road from the nearby town of Sayid Sadiq, fired artillery shells into Halabja, and the Air Force began dropping what is thought to have been napalm on the town, especially the northern area. Nasreen and Rangeen rushed to the cellar. Nasreen prayed that Bakhtiar, who was then outside the city, would find shelter.

The attack had ebbed by about two o'clock, and Nasreen made her way carefully upstairs to the kitchen, to get the food for the family. "At the end of the bombing, the sound changed," she said. "It wasn't so loud. It was like pieces of metal just dropping without exploding. We didn't know why it was so quiet."

A short distance away, in a neighborhood still called the Julakan, or Jewish quarter, even though Halabja's Jews left for Israel in the nineteen-fifties, a middle-aged man named Muhammad came up from his own cellar and saw an unusual sight: "A helicopter had come back to the town, and the soldiers were throwing white pieces of paper out the side." In retrospect, he understood that they were measuring wind speed and direction. Nearby, a man named Awat Omer, who was twenty at the time, was overwhelmed by a smell of garlic and apples.

Nasreen gathered the food quickly, but she, too, noticed a series of odd smells carried into the house by the wind. "At first, it smelled bad, like garbage," she said. "And then it was a good smell, like sweet apples. Then like eggs." Before she went downstairs, she happened to check on a caged partridge that her father kept in the house. "The bird was dying," she said. "It was on its side." She looked out the window. "It was very quiet, but the animals were dying. The sheep and goats were dying." Nasreen ran to the cellar. "I told everybody there was something wrong. There was something wrong with the air."

The people in the cellar were panicked. They had fled downstairs to escape the bombardment, and it was difficult to abandon their shelter. Only splinters of light penetrated the basement, but the dark provided a strange comfort. "We wanted to stay in hiding, even though we were getting sick," Nasreen said. She felt a sharp pain in her eyes, like stabbing needles. "My sister came close to my face and said, 'Your eyes are very red.' Then the children started throwing up. They kept throwing up. They were in so much pain, and crying so much. They were crying all the time. My mother was crying. Then the old people started throwing up."

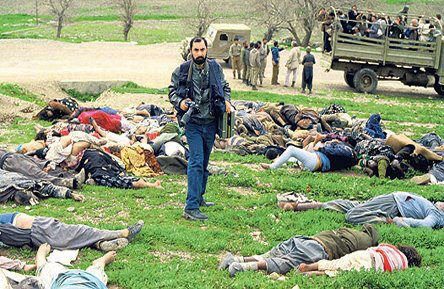

Chemical weapons had been dropped on Halabja by the Iraqi Air Force, which understood that any underground shelter would become a gas chamber. "My uncle said we should go outside," Nasreen said. "We knew there were chemicals in the air. We were getting red eyes, and some of us had liquid coming out of them. We decided to run." Nasreen and her relatives stepped outside gingerly. "Our cow was lying on its side," she recalled. "It was breathing very fast, as if it had been running. The leaves were falling off the trees, even though it was spring. The partridge was dead. There were smoke clouds around, clinging to the ground. The gas was heavier than the air, and it was finding the wells and going down the wells."

The family judged the direction of the wind, and decided to run the opposite way. Running proved difficult. "The children couldn't walk, they were so sick," Nasreen said. "They were exhausted from throwing up. We carried them in our arms."

Across the city, other families were making similar decisions. Nouri Hama Ali, who lived in the northern part of town, decided to lead his family in the direction of Anab, a collective settlement on the outskirts of Halabja that housed Kurds displaced when the Iraqi Army destroyed their villages. "On the road to Anab, many of the women and children began to die," Nouri told me. "The chemical clouds were on the ground. They were heavy. We could see them." People were dying all around, he said. When a child could not go on, the parents, becoming hysterical with fear, abandoned him. "Many children were left on the ground, by the side of the road. Old people as well. They were running, then they would stop breathing and die."

Nasreen's family did not move quickly. "We wanted to wash ourselves off and find water to drink," she said. "We wanted to wash the faces of the children who were vomiting. The children were crying for water. There was powder on the ground, white. We couldn't decide whether to drink the water or not, but some people drank the water from the well they were so thirsty."

They ran in a panic through the city, Nasreen recalled, in the direction of Anab. The bombardment continued intermittently, Air Force planes circling overhead. "People were showing different symptoms. One person touched some of the powder, and her skin started bubbling."

A truck came by, driven by a neighbor. People threw themselves aboard. "We saw people lying frozen on the ground," Nasreen told me. "There was a small baby on the ground, away from her mother. I thought they were both sleeping. But she had dropped the baby and then died. And I think the baby tried to crawl away, but it died, too. It looked like everyone was sleeping."

At that moment, Nasreen believed that she and her family would make it to high ground and live. Then the truck stopped. "The driver said he couldn't go on, and he wandered away. He left his wife in the back of the truck. He told us to flee if we could. The chemicals affected his brain, because why else would someone abandon his family?"

As heavy clouds of gas smothered the city, people became sick and confused. Awat Omer was trapped in his cellar with his family; he said that his brother began laughing uncontrollably and then stripped off his clothes, and soon afterward he died. As night fell, the family's children grew sicker—too sick to move.

Nasreen's husband could not be found, and she began to think that all was lost. She led the children who were able to walk up the road.

In another neighborhood, Muhammad Ahmed Fattah, who was twenty, was overwhelmed by an oddly sweet odor of sulfur, and he, too, realized that he must evacuate his family; there were about a hundred and sixty people wedged into the cellar. "I saw the bomb drop," Muhammad told me. "It was about thirty metres from the house. I shut the door to the cellar. There was shouting and crying in the cellar, and then people became short of breath." One of the first to be stricken by the gas was Muhammad's brother Salah. "His eyes were pink," Muhammad recalled. "There was something coming out of his eyes. He was so thirsty he was demanding water." Others in the basement began suffering tremors.

March 16th was supposed to be Muhammad's wedding day. "Every preparation was done," he said. His fiancée, a woman named Bahar Jamal, was among the first in the cellar to die. "She was crying very hard," Muhammad recalled. "I tried to calm her down. I told her it was just the usual artillery shells, but it didn't smell the usual way weapons smelled. She was smart, she knew what was happening. She died on the stairs. Her father tried to help her, but it was too late."

Death came quickly to others as well. A woman named Hamida Mahmoud tried to save her two-year-old daughter by allowing her to nurse from her breast. Hamida thought that the baby wouldn't breathe in the gas if she was nursing, Muhammad said, adding, "The baby's name was Dashneh. She nursed for a long time. Her mother died while she was nursing. But she kept nursing." By the time Muhammad decided to go outside, most of the people in the basement were unconscious; many were dead, including his parents and three of his siblings.

Nasreen said that on the road to Anab all was confusion. She and the children were running toward the hills, but they were going blind. "The children were crying, 'We can't see! My eyes are bleeding!' " In the chaos, the family got separated. Nasreen's mother and father were both lost. Nasreen and several of her cousins and siblings inadvertently led the younger children in a circle, back into the city. Someone—she doesn't know who—led them away from the city again and up a hill, to a small mosque, where they sought shelter. "But we didn't stay in the mosque, because we thought it would be a target," Nasreen said. They went to a small house nearby, and Nasreen scrambled to find food and water for the children. By then, it was night, and she was exhausted.

Bakhtiar, Nasreen's husband, was frantic. Outside the city when the attacks started, he had spent much of the day searching for his wife and the rest of his family. He had acquired from a clinic two syringes of atropine, a drug that helps to counter the effects of nerve agents. He injected himself with one of the syringes, and set out to find Nasreen. He had no hope. "My plan was to bury her," he said. "At least I should bury my new wife."

After hours of searching, Bakhtiar met some neighbors, who remembered seeing Nasreen and the children moving toward the mosque on the hill. "I called out the name Nasreen," he said. "I heard crying, and I went inside the house. When I got there, I found that Nasreen was alive but blind. Everybody was blind."

Nasreen had lost her sight about an hour or two before Bakhtiar found her. She had been searching the house for food, so that she could feed the children, when her eyesight failed. "I found some milk and I felt my way to them and then I found their mouths and gave them milk," she said.

Bakhtiar organized the children. "I wanted to bring them to the well. I washed their heads. I took them two by two and washed their heads. Some of them couldn't come. They couldn't control their muscles."

Bakhtiar still had one syringe of atropine, but he did not inject his wife; she was not the worst off in the group. "There was a woman named Asme, who was my neighbor," Bakhtiar recalled. "She was not able to breathe. She was yelling and she was running into a wall, crashing her head into a wall. I gave the atropine to this woman." Asme died soon afterward. "I could have used it for Nasreen," Bakhtiar said. "I could have."

After the Iraqi bombardment subsided, the Iranians managed to retake Halabja, and they evacuated many of the sick, including Nasreen and the others in her family, to hospitals in Tehran.

Nasreen was blind for twenty days. "I was thinking the whole time, Where is my family? But I was blind. I couldn't do anything. I asked my husband about my mother, but he said he didn't know anything. He was looking in hospitals, he said. He was avoiding the question."

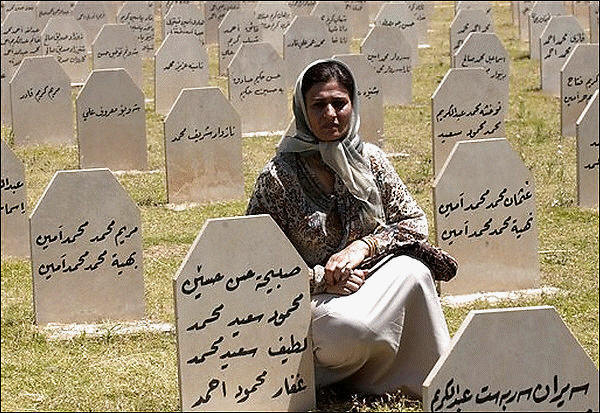

The Iranian Red Crescent Society, the equivalent of the Red Cross, began compiling books of photographs, pictures of the dead in Halabja. "The Red Crescent has an album of the people who were buried in Iran," Nasreen said. "And we found my mother in one of the albums." Her father, she discovered, was alive but permanently blinded. Five of her siblings, including Rangeen, had died.

Nasreen would live, the doctors said, but she kept a secret from Bakhtiar: "When I was in the hospital, I started menstruating. It wouldn't stop. I kept bleeding. We don't talk about this in our society, but eventually a lot of women in the hospital confessed they were also menstruating and couldn't stop." Doctors gave her drugs that stopped the bleeding, but they told her that she would be unable to bear children.

Nasreen stayed in Iran for several months, but eventually she and Bakhtiar returned to Kurdistan. She didn't believe the doctors who told her that she would be infertile, and in 1991 she gave birth to a boy. "We named him Arazoo," she said. Arazoo means hope in Kurdish. "He was healthy at first, but he had a hole in his heart. He died at the age of three months."

I met Nasreen last month in Erbil, the largest city in Iraqi Kurdistan. She is thirty now, a pretty woman with brown eyes and high cheekbones, but her face is expressionless. She doesn't seek pity; she would, however, like a doctor to help her with a cough that she's had ever since the attack, fourteen years ago. Like many of Saddam Hussein's victims, she tells her story without emotion.

During my visit to Kurdistan, I talked with more than a hundred victims of Saddam's campaign against the Kurds. Saddam has been persecuting the Kurds ever since he took power, more than twenty years ago. Several old women whose husbands were killed by Saddam's security services expressed a kind of animal hatred toward him, but most people, like Nasreen, told stories of horrific cruelty with a dispassion and a precision that underscored their credibility. Credibility is important to the Kurds; after all this time, they still feel that the world does not believe their story.

A week after I met Nasreen, I visited a small village called Goktapa, situated in a green valley that is ringed by snow-covered mountains. Goktapa came under poison-gas attack six weeks after Halabja. The village consists of low mud-brick houses along dirt paths. In Goktapa, an old man named Ahmed Raza Sharif told me that on the day of the attack on Goktapa, May 3, 1988, he was in the fields outside the village. He saw the shells explode and smelled the sweet-apple odor as poison filled the air. His son, Osman Ahmed, who was sixteen at the time, was near the village mosque when he was felled by the gas. He crawled down a hill and died among the reeds on the banks of the Lesser Zab, the river that flows by the village. His father knew that he was dead, but he couldn't reach the body. As many as a hundred and fifty people died in the attack; the survivors fled before the advancing Iraqi Army, which levelled the village. Ahmed Raza Sharif did not return for three years. When he did, he said, he immediately began searching for his son's body. He found it still lying in the reeds. "I recognized his body right away," he said.

The summer sun in Iraq is blisteringly hot, and a corpse would be unidentifiable three years after death. I tried to find a gentle way to express my doubts, but my translator made it clear to Sharif that I didn't believe him.

We were standing in the mud yard of another old man, Ibrahim Abdul Rahman. Twenty or thirty people, a dozen boys among them, had gathered. Some of them seemed upset that I appeared to doubt the story, but Ahmed hushed them. "It's true, he lost all the flesh on his body," he said. "He was just a skeleton. But the clothes were his, and they were still on the skeleton, a belt and a shirt. In the pocket of his shirt I found the key to our tractor. That's where he always kept the key."

Some of the men still seemed concerned that I would leave Goktapa doubting their truthfulness. Ibrahim, the man in whose yard we were standing, called out a series of orders to the boys gathered around us. They dispersed, to houses and storerooms, returning moments later holding jagged pieces of metal, the remnants of the bombs that poisoned Goktapa. Ceremoniously, the boys dropped the pieces of metal at my feet. "Here are the mercies of Uncle Saddam," Ibrahim said.

THE AFTERMATH

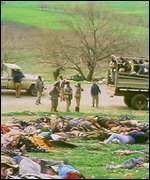

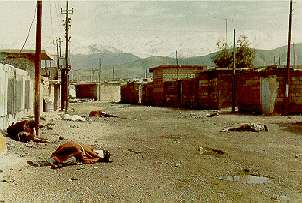

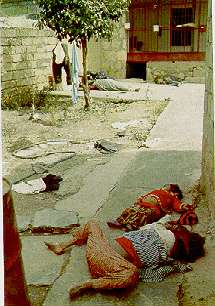

The story of Halabja did not end the night the Iraqi Air Force planes returned to their bases. The Iranians invited the foreign press to record the devastation. Photographs of the victims, supine, bleached of color, littering the gutters and alleys of the town, horrified the world. Saddam Hussein's attacks on his own citizens mark the only time since the Holocaust that poison gas has been used to exterminate women and children.

Saddam's cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, who led the campaigns against the Kurds in the late eighties, was heard on a tape captured by rebels, and later obtained by Human Rights Watch, addressing members of Iraq's ruling Baath Party on the subject of the Kurds. "I will kill them all with chemical weapons!" he said. "Who is going to say anything? The international community? Fuck them! The international community and those who listen to them."

Attempts by Congress in 1988 to impose sanctions on Iraq were stifled by the Reagan and Bush Administrations, and the story of Saddam's surviving victims might have vanished completely had it not been for the reporting of people like Randal and the work of a British documentary filmmaker named Gwynne Roberts, who, after hearing stories about a sudden spike in the incidence of birth defects and cancers, not only in Halabja but also in other parts of Kurdistan, had made some disturbing films on the subject. However, no Western government or United Nations agency took up the cause.

In 1998, Roberts brought an Englishwoman named Christine Gosden to Kurdistan. Gosden is a medical geneticist and a professor at the medical school of the University of Liverpool. She spent three weeks in the hospitals in Kurdistan, and came away determined to help the Kurds. To the best of my knowledge, Gosden is the only Western scientist who has even begun making a systematic study of what took place in northern Iraq.

Gosden told me that her father was a high-ranking officer in the Royal Air Force, and that as a child she lived in Germany, near Bergen-Belsen. "It's tremendously influential in your early years to live near a concentration camp," she said. In Kurdistan, she heard echoes of the German campaign to destroy the Jews. "The Iraqi government was using chemistry to reduce the population of Kurds," she said. "The Holocaust is still having its effect. The Jews are fewer in number now than they were in 1939. That's not natural. Now, if you take out two hundred thousand men and boys from Kurdistan"—an estimate of the number of Kurds who were gassed or otherwise murdered in the campaign, most of whom were men and boys—"you've affected the population structure. There are a lot of widows who are not having children."

Richard Butler, an Australian diplomat who chaired the United Nations weapons-inspection team in Iraq, describes Gosden as "a classic English, old-school-tie kind of person." Butler has tracked her research since she began studying the attacks, four years ago, and finds it credible. "Occasionally, people say that this is Christine's obsession, but obsession is not a bad thing," he added.

Before I went to Kurdistan, in January, I spent a day in London with Gosden. We gossiped a bit, and she scolded me for having visited a Washington shopping mall without appropriate protective equipment. Whenever she goes to a mall, she brings along a polyurethane bag "big enough to step into" and a bottle of bleach. "I can detoxify myself immediately," she said.

Gosden believes it is quite possible that the countries of the West will soon experience chemical- and biological-weapons attacks far more serious and of greater lasting effect than the anthrax incidents of last autumn and the nerve-agent attack on the Tokyo subway system several years ago—that what happened in Kurdistan was only the beginning. "For Saddam's scientists, the Kurds were a test population," she said. "They were the human guinea pigs. It was a way of identifying the most effective chemical agents for use on civilian populations, and the most effective means of delivery."

The charge is supported by others. An Iraqi defector, Khidhir Hamza, who is the former director of Saddam's nuclear-weapons program, told me earlier this year that before the attack on Halabja military doctors had mapped the city, and that afterward they entered it wearing protective clothing, in order to study the dispersal of the dead. "These were field tests, an experiment on a town," Hamza told me. He said that he had direct knowledge of the Army's procedures that day in Halabja. "The doctors were given sheets with grids on them, and they had to answer questions such as 'How far are the dead from the cannisters?' "

Gosden said that she cannot understand why the West has not been more eager to investigate the chemical attacks in Kurdistan. "It seems a matter of enlightened self-interest that the West would want to study the long-term effects of chemical weapons on civilians, on the DNA," she told me. "I've seen Europe's worst cancers, but, believe me, I have never seen cancers like the ones I saw in Kurdistan."

According to an ongoing survey conducted by a team of Kurdish physicians and organized by Gosden and a small advocacy group called the Washington Kurdish Institute, more than two hundred towns and villages across Kurdistan were attacked by poison gas—far more than was previously thought—in the course of seventeen months. The number of victims is unknown, but doctors I met in Kurdistan believe that up to ten per cent of the population of northern Iraq—nearly four million people—has been exposed to chemical weapons. "Saddam Hussein poisoned northern Iraq," Gosden said when I left for Halabja. "The questions, then, are what to do? And what comes next?"

HALABJA'S DOCTORS

The Kurdish people, it is often said, make up the largest stateless nation in the world. They have been widely despised by their neighbors for centuries. There are roughly twenty-five million Kurds, most of them spread across four countries in southwestern Asia: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. The Kurds are neither Arab, Persian, nor Turkish; they are a distinct ethnic group, with their own culture and language. Most Kurds are Muslim (the most famous Muslim hero of all, Saladin, who defeated the Crusaders, was of Kurdish origin), but there are Jewish and Christian Kurds, and also followers of the Yezidi religion, which has its roots in Sufism and Zoroastrianism. The Kurds are experienced mountain fighters, who tend toward stubbornness and have frequent bouts of destructive infighting.

After centuries of domination by foreign powers, the Kurds had their best chance at independence after the First World War, when President Woodrow Wilson promised the Kurds, along with other groups left drifting and exposed by the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, a large measure of autonomy. But the machinations of the great powers, who were becoming interested in Kurdistan's vast oil deposits, in Mosul and Kirkuk, quickly did the Kurds out of a state.

In the nineteen-seventies, the Iraqi Kurds allied themselves with the Shah of Iran in a territorial dispute with Iraq. America, the Shah's patron, once again became the Kurds' patron, too, supplying them with arms for a revolt against Baghdad. But a secret deal between the Iraqis and the Shah, arranged in 1975 by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, cut off the Kurds and brought about their instant collapse; for the Kurds, it was an ugly betrayal.

The Kurdish safe haven, in northern Iraq, was born of another American betrayal. In 1991, after the United States helped drive Iraq out of Kuwait, President George Bush ignored an uprising that he himself had stoked, and Kurds and Shiites in Iraq were slaughtered by the thousands. Thousands more fled the country, the Kurds going to Turkey, and almost immediately creating a humanitarian disaster. The Bush Administration, faced with a televised catastrophe, declared northern Iraq a no-fly zone and thus a safe haven, a tactic that allowed the refugees to return home. And so, under the protective shield of the United States and British Air Forces, the unplanned Kurdish experiment in self-government began. Although the Kurdish safe haven is only a virtual state, it is an incipient democracy, a home of progressive Islamic thought and pro-American feeling.

Today, Iraqi Kurdistan is split between two dominant parties: the Kurdistan Democratic Party, led by Massoud Barzani, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, whose General Secretary is Jalal Talabani. The two parties have had an often angry relationship, and in the mid-nineties they fought a war that left about a thousand soldiers dead. The parties, realizing that they could not rule together, decided to rule apart, dividing Kurdistan into two zones. The internal political divisions have not aided the Kurds' cause, but neighboring states also have fomented disunity, fearing that a unified Kurdish population would agitate for independence.

Turkey, with a Kurdish population of between fifteen and twenty million, has repressed the Kurds in the eastern part of the country, politically and militarily, on and off since the founding of the modern Turkish state. In 1924, the government of Atatürk restricted the use of the Kurdish language (a law not lifted until 1991) and expressions of Kurdish culture; to this day, the Kurds are referred to in nationalist circles as "mountain Turks."

Turkey is not eager to see Kurds anywhere draw attention to themselves, which is why the authorities in Ankara refused to let me cross the border into Iraqi Kurdistan. Iran, whose Kurdish population numbers between six and eight million, was not helpful, either, and my only option for gaining entrance to Kurdistan was through its third neighbor, Syria. The Kurdistan Democratic Party arranged for me to be met in Damascus and taken to the eastern desert city of El Qamishli. From there, I was driven in a Land Cruiser to the banks of the Tigris River, where a small wooden boat, with a crew of one and an outboard motor, was waiting. The engine spluttered; when I learned that the forward lines of the Iraqi Army were two miles downstream, I began to paddle, too. On the other side of the river were representatives of the Kurdish Democratic Party and the peshmerga, the Kurdish guerrillas, who wore pantaloons and turbans and were armed with AK-47s.

"Welcome to Kurdistan" read a sign at the water's edge greeting visitors to a country that does not exist.

Halabja is a couple of hundred miles from the Syrian border, and I spent a week crossing northern Iraq, making stops in the cities of Dahuk and Erbil on the way. I was handed over to representatives of the Patriotic Union, which controls Halabja, at a demilitarized zone west of the town of Koysinjaq. From there, it was a two-hour drive over steep mountains to Sulaimaniya, a city of six hundred and fifty thousand, which is the cultural capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. In Sulaimaniya, I met Fouad Baban, one of Kurdistan's leading physicians, who promised to guide me through the scientific and political thickets of Halabja.

Baban, a pulmonary and cardiac specialist who has survived three terms in Iraqi prisons, is sixty years old, and a man of impish good humor. He is the Kurdistan coördinator of the Halabja Medical Institute, which was founded by Gosden, Michael Amitay, the executive director of the Washington Kurdish Institute, and a coalition of Kurdish doctors; for the doctors, it is an act of bravery to be publicly associated with a project whose scientific findings could be used as evidence if Saddam Hussein faced a war-crimes tribunal. Saddam's agents are everywhere in the Kurdish zone, and his tanks sit forty miles from Baban's office.

Soon after I arrived in Sulaimaniya, Baban and I headed out in his Toyota Camry for Halabja. On a rough road, we crossed the plains of Sharazoor, a region of black earth and honey-colored wheat ringed by jagged, snow-topped mountains. We were not travelling alone. The Mukhabarat, the Iraqi intelligence service, is widely reported to have placed a bounty on the heads of Western journalists caught in Kurdistan (either ten thousand dollars or twenty thousand dollars, depending on the source of the information). The areas around the border with Iran are filled with Tehran's spies, and members of Ansar al-Islam, an Islamist terror group, were said to be decapitating people in the Halabja area. So the Kurds had laid on a rather elaborate security detail. A Land Cruiser carrying peshmerga guerrillas led the way, and we were followed by another Land Cruiser, on whose bed was mounted an anti-aircraft weapon manned by six peshmerga, some of whom wore black balaclavas. We were just south of the American- and British-enforced no-fly zone. I had been told that, at the beginning of the safe-haven experiment, the Americans had warned Saddam's forces to stay away; a threat from the air, though unlikely, was, I deduced, not out of the question.

"It seems very important to know the immediate and long-term effects of chemical and biological weapons," Baban said, beginning my tutorial. "Here is a civilian population exposed to chemical and possibly biological weapons, and people are developing many varieties of cancers and congenital abnormalities. The Americans are vulnerable to these weapons—they are cheap, and terrorists possess them. So, after the anthrax attacks in the States, I think it is urgent for scientific research to be done here."

Experts now believe that Halabja and other places in Kurdistan were struck by a combination of mustard gas and nerve agents, including sarin (the agent used in the Tokyo subway attack) and VX, a potent nerve agent. Baban's suggestion that biological weapons may also have been used surprised me. One possible biological weapon that Baban mentioned was aflatoxin, which causes long-term liver damage.

A colleague of Baban's, a surgeon who practices in Dahuk, in northwestern Kurdistan, and who is a member of the Halabja Medical Institute team, told me more about the institute's survey, which was conducted in the Dahuk region in 1999. The surveyors began, he said, by asking elementary questions; eleven years after the attacks, they did not even know which villages had been attacked.

"The team went to almost every village," the surgeon said. "At first, we thought that the Dahuk governorate was the least affected. We knew of only two villages that were hit by the attacks. But we came up with twenty-nine in total. This is eleven years after the fact."

The surgeon is professorial in appearance, but he is deeply angry. He doubles as a pediatric surgeon, because there are no pediatric surgeons in Kurdistan. He has performed more than a hundred operations for cleft palate on children born since 1988. Most of the agents believed to have been dropped on Halabja have short half-lives, but, as Baban told me, "physicians are unsure how long these toxins will affect the population. How can we know agent half-life if we don't know the agent?" He added, "If we knew the toxins that were used, we could follow them and see actions on spermatogenesis and ovogenesis."

Increased rates of infertility, he said, are having a profound effect on Kurdish society, which places great importance on large families. "You have men divorcing their wives because they could not give birth, and then marrying again, and then their second wives can't give birth, either," he said. "Still, they don't blame their own problem with spermatogenesis."

Baban told me that the initial results of the Halabja Medical Institute-sponsored survey show abnormally high rates of many diseases. He said that he compared rates of colon cancer in Halabja with those in the city of Chamchamal, which was not attacked with chemical weapons. "We are seeing rates of colon cancer five times higher in Halabja than in Chamchamal," he said.

There are other anomalies as well, Baban said. The rate of miscarriage in Halabja, according to initial survey results, is fourteen times the rate of miscarriage in Chamchamal; rates of infertility among men and women in the affected population are many times higher than normal. "We're finding Hiroshima levels of sterility," he said.

Then, there is the suspicion about snakes. "Have you heard about the snakes?" he asked as we drove. I told him that I had heard rumors. "We don't know if a genetic mutation in the snakes has made them more toxic," Baban went on, "or if the birds that eat the snakes were killed off in the attacks, but there seem to be more snakebites, of greater toxicity, in Halabja now than before." (I asked Richard Spertzel, a scientist and a former member of the United Nations Special Commission inspections team, if this was possible. Yes, he said, but such a rise in snakebites was more likely due to "environmental imbalances" than to mutations.)

My conversation with Baban was suddenly interrupted by our guerrilla escorts, who stopped the car and asked me to join them in one of the Land Cruisers; we veered off across a wheat field, without explanation. I was later told that we had been passing a mountain area that had recently had problems with Islamic terrorists.

We arrived in Halabja half an hour later. As you enter the city, you see a small statue modelled on the most famous photographic image of the Halabja massacre: an old man, prone and lifeless, shielding his dead grandson with his body.

A torpor seems to afflict Halabja; even its bazaar is listless and somewhat empty, in marked contrast to those of other Kurdish cities, which are well stocked with imported goods (history and circumstance have made the Kurds enthusiastic smugglers) and are full of noise and activity. "Everyone here is sick," a Halabja doctor told me. "The people who aren't sick are depressed." He practices at the Martyrs' Hospital, which is situated on the outskirts of the city. The hospital has no heat and little advanced equipment; like the city itself, it is in a dilapidated state.

The doctor is a thin, jumpy man in a tweed jacket, and he smokes without pause. He and Baban took me on a tour of the hospital. Afterward, we sat in a bare office, and a woman was wheeled in. She looked seventy but said that she was fifty; doctors told me she suffers from lung scarring so serious that only a lung transplant could help, but there are no transplant centers in Kurdistan. The woman, whose name is Jayran Muhammad, lost eight relatives during the attack. Her voice was almost inaudible. "I was disturbed psychologically for a long time," she told me as Baban translated. "I believed my children were alive." Baban told me that her lungs would fail soon, that she could barely breathe. "She is waiting to die," he said. I met another woman, Chia Hammassat, who was eight at the time of the attacks and has been blind ever since. Her mother, she said, died of colon cancer several years ago, and her brother suffers from chronic shortness of breath. "There is no hope to correct my vision," she said, her voice flat. "I was married, but I couldn't fulfill the responsibilities of a wife because I'm blind. My husband left me."

Baban said that in Halabja "there are more abnormal births than normal ones," and other Kurdish doctors told me that they regularly see children born with neural-tube defects and undescended testes and without anal openings. They are seeing—and they showed me—children born with six or seven toes on each foot, children whose fingers and toes are fused, and children who suffer from leukemia and liver cancer.

I met Sarkar, a shy and intelligent boy with a harelip, a cleft palate, and a growth on his spine. Sarkar had a brother born with the same set of malformations, the doctor told me, but the brother choked to death, while still a baby, on a grain of rice.

Meanwhile, more victims had gathered in the hallway; the people of Halabja do not often have a chance to tell their stories to foreigners. Some of them wanted to know if I was a surgeon, who had come to repair their children's deformities, and they were disappointed to learn that I was a journalist. The doctor and I soon left the hospital for a walk through the northern neighborhoods of Halabja, which were hardest hit in the attack. We were trailed by peshmerga carrying AK-47s. The doctor smoked as we talked, and I teased him about his habit. "Smoking has some good effect on the lungs," he said, without irony. "In the attacks, there was less effect on smokers. Their lungs were better equipped for the mustard gas, maybe."

We walked through the alleyways of the Jewish quarter, past a former synagogue in which eighty or so Halabjans died during the attack. Underfed cows wandered the paths. The doctor showed me several cellars where clusters of people had died. We knocked on the gate of one house, and were let in by an old woman with a wide smile and few teeth. In the Kurdish tradition, she immediately invited us for lunch.

She told us the recent history of the house. "Everyone who was in this house died," she said. "The whole family. We heard there were one hundred people." She led us to the cellar, which was damp and close. Rusted yellow cans of vegetable ghee littered the floor. The room seemed too small to hold a hundred people, but the doctor said that the estimate sounded accurate. I asked him if cellars like this one had ever been decontaminated. He smiled. "Nothing in Kurdistan has been decontaminated," he said.